Sept. 9, 2015 It’s been an insightful, wild ride learning about the kids app industry…from the “Inside, Out.”

Sept. 9, 2015 It’s been an insightful, wild ride learning about the kids app industry…from the “Inside, Out.”

In Part One we talked about the imperative need for transparency and media literacy in children’s app reviews with “expedited review” paid policies not being readily disclosed…

In Part Two we focused on the face-off between app developers and reviewers about the ethics and business policies of paying for press coverage in a ratings environment that’s all over the kids media sphere in terms of quality control.

Ideas and solutions? Anyone?

In Part Three, we’ll ask those those with firsthand experience whether ‘expedited reviews’ even work, what fee for service media coverage does to an increasingly jaded public, and whether indie entrepreneurs are resigned to market conditions of big fish gulping the minnows. What’s it gonna be?

Makers and creatives may try to work collaboratively with commercial interests, brands, and tech titans but the fragile startup ecosystem is increasingly favoring behemoths over diversity, formulas over originality, and volume and displacement over smaller, experiential quirkiness.

Big Cruise Ships vs Indie Yachts

Big Cruise Ships vs Indie Yachts

Small indie app developers with limited budgets and tiny promo teams vs large commercial brands that can buy mass exposure and paid PR/reviews obviously creates a sea of media and monetization mayhem.

It’s the difference between a massive cruise ship with a full infrastructure docking at a large pier in a well-traveled port of call versus an intimate yacht charter exploring islands off the beaten path using tinders and Zodiacs to gain access…both offer a markedly different experience, with merits and consumer choice a considerable factor.

While mass offerings can tip the scales of profitability toward volume, it also can create formulaic sameness, altering the sustainability of the smaller offerings altogether…It most certainly impacts how many ‘ports of call’ small entities with complex itineraries can afford. These shifts in monetization methods create invariable consequences, something that requires circumspect thought before inadvertently dragging a heavy anchor across a fragile coral reef creating irreversible damage, because that can destroy the reef growth forever. (end of creative/innovation analogy, and yes, I AM a water rat.)

With Volume Increase, Indie Voices Decrease

TechCrunch reported at the Worldwide Developers Conference that there are now 850 apps downloaded every second, so it stands to reason the kids app marketplace has also become substantially overwhelmed in just the last year alone. The sheer volume is daunting.

“Sites come and go constantly from this space because there is no way to make a working wage reviewing apps,” said Carisa Kluver of Digital Storytime.

“I fear it is much like other areas where the break-down in paid sources where journalists can do reviews has left only a small handful of outlets… With apps the issue is much greater than it is for say, feature films. There are simply too many apps and eBooks being published today for anyone to possibly review, let alone read.

This means even exceptional content will not be covered unless the developers consider ‘expedited’ site reviews (and even paid or quid pro quo reviews on iTunes, Amazon, Google-Play, etc.) The ‘gaming’ of the system is open season as a result. It is very hard to tell, however, if this pay-to-play hasn’t always been in operation with ‘trusted’ journalistic outlets… perhaps the only difference is the web has been more transparent?”

2014 to 2015: Big Shifts in the Last Year

Special education teacher Libby Curran also noted the volume to reply ratios shifting in her own feedback with respected reviewers:

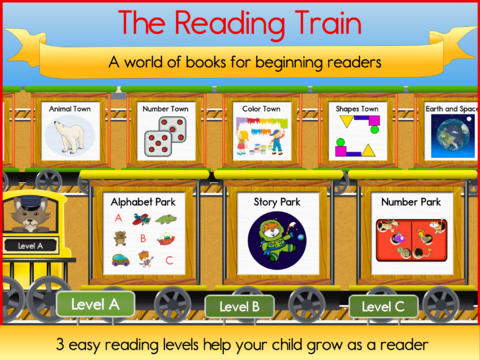

“In Feb. 2014 TeachersWithApps.com and SmartAppsForSpecialNeeds.com both wrote glowing reviews of my app… Although they offered expedited reviews at the time, and stated that there could be a 6-12 week wait for a free review, they felt Reading Train was an app worthy of inclusion and reviewed it very quickly for free. When I submitted a request for a new app March 2015, smartappsforkids.com sent me this reply-

‘Due to demand we are only publishing paid Priority Reviews (prices start at $175) Another cheaper alternative you can consider in the future is to update Heather’s post with the new information and link – the cost of this is $100.’

…Included was a link for info on all 26 paid items. I believe Teachers With Apps still may offer free reviews, but my request for a free review was made 5 months ago with no reply.”

New Money Models: Quantity Impacts Quality

App developers repeatedly voiced the need for some sort of ‘list’ compilation to clearly delineate at a glance who charges and who doesn’t to cut through the clutter.

Many suggested anonymous forums for sharing collective knowledge would be helpful if identities could be protected and preserved. (again, fear of reprisals and clout of reviewers is complicated by the antics and ‘small world’ stage of this industry)

Conversely, I noticed some new sites like App Apes launched just within the last year seem to be expanding on the AppyNation list mentioned earlier calling out who’s doing what and then attempting to monetize by gleaning traffic and a peer review/pay it forward approach. (which seems like a boldly idyllic collaboration idea but perhaps a logistical quality control nightmare)

They’ve posted articles highlighting ‘paid vs unpaid’ app review opportunities and critical thinking assessments like this one titled “Developers Beware of the AndroidPIT” and though their site looks current, the App Apes Twitter account appears dormant now for several months…which makes me wonder if it’s indicative of how fast and fleeting cavalry calls to rescue review sites ends up with good intentions sinking into the quicksand of overload. (especially as sites jockey for ‘bigger better best’ joining the pile of opinions and review site roundups) Meanwhile, I asked a few reviewers themselves:

“Beyond quantity of apps and overwhelm, what’s changed lately…And why?”

When Everybody Wins, No One Does

Star gazing (and navel gazing)

One popular app reviewer pointed to her former employer, a respected hub site, and line by line compared the same app in ‘that was then this is now’ detail pointing to a puffed up ‘extra star’ and heavily implying a ‘dumbed down’ “everybody gets a trophy” form of fluff and stuff ratings systems due to the site’s new emphasis on free apps and click-throughs to serve ad impressions, plus the influence of the advertisers themselves.

Higher stars, lower standards, baseline shifts

The ‘page view’ polka creates a dance of a different tempo altogether. Quality, in-depth coverage can give way to copious ‘free app’ banners and bland prose regurgitating sameness.

One prolific pundit with over 1000 reviews to her name noted that previously apps were ‘RARELY given 5 stars’ and now she’s seen money-based edit decisions, sloppy reporting and abysmal proofreading on both the developer and reviewer end (some with language barriers in app descriptions) including one education app with eight grammatical errors that still yielded a high-starred review!

As an educator, she was offended and left commentary on the standards put forth, only to be threatened and blackmailed to ‘take it down’ from the app store site in ‘you’ll never work in this industry again’ movie-style intimidation.

Sheesh. There’s more “bad blood” in this business than a Taylor Swift tune…

(Sidebar on sloppiness: I can attest to my own raised eyebrows seeing countless typos and misspellings from ed tech specialists and teachers emailing their feedback to me from part one, and admit thinking, “wait, THESE are education reviewers?” Seriously? Ahem.)

Journalists for Hire: Credibility for Cash

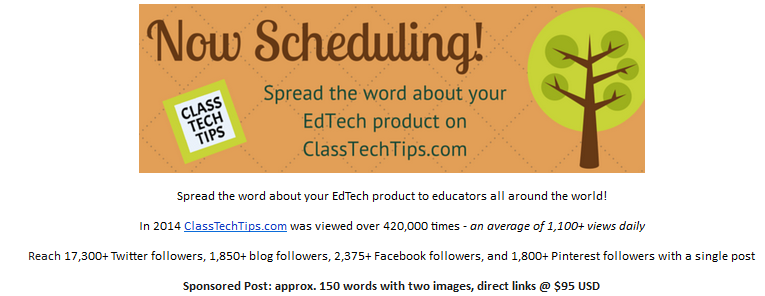

In addition to the “big budget/big visibility” issue, journalists well known for review writing are also running their own ventures creating increasingly influential brand personas. I hadn’t seen some of the e-blasts directly, since app reviews are not in my usual media literacy wheelhouse, but my “open call for feedback” lobbed some interesting material my way, such as this sample, explaining the editorial blogging process in a sound bite: “Are you ready to get the word out?”

“You send the key points and images – I write the post, share a preview with you, and send an invoice for payment via Paypal.”

Well, gosh. Okay. No doubt this is normative these days, as that’s straightforward, and clearly transparent…But here’s where I derail in ‘old school’ journalism mode:

This editorial service is provided by Class Tech Tips, run by a respected writer and thorough reviewer who is also a regular contributor to Edutopia.org an ed tech and curriculum consultant, an Apple Distinguished Educator, webinar host for Simple K12, regular contributor to Channel One classroom news, and so on. Scrolling through her helpful slideshares for teachers I kept thinking, “wow, that’s some substantive street cred” but now I’m wondering what is or isn’t paid for, who was or wasn’t a client, as the influence packs a powerful punch extending to multiple media channels inside and outside the classroom…

Once upon a time, writers simply could NOT wear both hats, as it was perceived as “double dipping.”

Journalistic influence and currying favor with media mavens used to be forboden, but in today’s “content marketing” era, conflict of interest seems to have blurred lines (or erased them altogether) as discussed at length in part two of this series. No matter how transparent paid reviewers might be, a handful of individuals should not be the only arbiters of taste, in an industry teeming with self-awarded authority. As it is, surveys say the public (parents! purchasers!) don’t have a clue about who’s who and content disclosures, that’s problematic.

What else has changed?

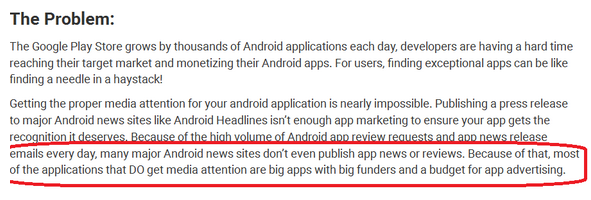

The entire tonality and acceptance of paid reviews. Compare the industry normalization of 2015 “Appvertising” with just a few years ago in 2012, when headlines sounding dubious and nefarious dominated the app news landscape…“iPhone Paid Sites Outed” or “Review Sites Caught Charging.”

Today? The bow to big funding and hefty app budgets seems to be ‘situation normal’ as this matter of fact promo pitch from Android Headlines puts forth here in this screenshot below:

Many app developers shoulder shrug with resignation that this is an inevitability now…If so, that means the ‘oceanliners’ are sailing right over the private yachts…and that’s a sea change I personally don’t want to see, as cookie cutter sameness and formulaic franchises are already dominating the film world, we don’t need apps to go the same route squelching originality and innovation.

While most developers did not begrudge app reviewers the right to charge a fee for service, many were clearly irked at the lopsided power base, and all were adamant paid reviews should be clearly marked and preferably sniped with a ‘sponsored ad’ disclosure similar to social media ads on Facebook or Twitter.

Again, there’s an inherent conflict of interest when indie reviewers need the money to operate and continue – yet their value comes from providing valid and accurate reviews, preferably on a wide array of review sites where they’ve self-established as an expert in the field.

I approached a few teachers with testimonials in promotional pitches, like the one for ClassTechTips.com above…

Chris Hull, a seventh grade social studies teacher and Chief Product Officer for Otus, a learning management system, explained why he found value using independent review sites, especially in the highly specialized realm of education apps:

“As a teacher I hope the reviews are unbiased and provide helpful information to enable the use of these educational tools to help student learning, as my driving philosophy for both roles is to help student learning…

…”As a CPO working at Otus, I know how important these reviews can be to creating buzz, new users, and validation that the tool(s) created are helpful. Ideally, you can have reviews build upon each other in a wave of positive attention and exposure. The timing of these reviews can be critical. If a product is adding new features or a press release will soon be announcing additional partnerships you want to work with these reviewers to ensure the best timing.”

Karen Mahon founder of ed tech review site Bale Fire Labs indicated there really is no money in ed app review sites, and echoed a public service lens purpose to elevate student learning:

“Many of us whose efforts are NOT underwritten by bigger businesses or funded by private foundations got into this to try to make a contribution to education. Most of us are kind of mission-oriented and looking to help teachers and kids…But it’s just not clear that very many teachers and parents value the information that we, as a group, provide.

We know that, for the most part, they are not willing to pay for our expertise and information. And I don’t think that we, as a group, have figured out a successful business model to do this work. Nobody goes into app reviewing with illusions of getting rich.”

In a hefty, thorough analysis in the comments section of Shaping Youth’s part two, Native Brain math curricula founder Michael Connell, Ed.D offered a must read critique about misalignment in this sphere (pointing to the inherent disconnect of the loose terminology surrounding the word “educational” along with “lack of standards for what qualifies as educational, ad hoc, inconsistent and irrelevant evaluation criteria, financial misalignment, bias lack of fairness” etc.) On the latter, he shared some positive points about his own experiences:

In a hefty, thorough analysis in the comments section of Shaping Youth’s part two, Native Brain math curricula founder Michael Connell, Ed.D offered a must read critique about misalignment in this sphere (pointing to the inherent disconnect of the loose terminology surrounding the word “educational” along with “lack of standards for what qualifies as educational, ad hoc, inconsistent and irrelevant evaluation criteria, financial misalignment, bias lack of fairness” etc.) On the latter, he shared some positive points about his own experiences:

![]() “To your question about fairness, Balefire Labs and Teachers With Apps were the ONLY reviewers who reviewed our app during this time without a fee even though we reached out or submitted it to many. (Note that once we started getting some traction a few others did pick up on it later.)

“To your question about fairness, Balefire Labs and Teachers With Apps were the ONLY reviewers who reviewed our app during this time without a fee even though we reached out or submitted it to many. (Note that once we started getting some traction a few others did pick up on it later.)

Regarding TWA, not only did they review the app but they put it into the hands of students and observed them using it. I believe this practice helps limit at least one important form of bias – where adults try to imagine children’s experience with the app without giving it to multiple children in the appropriate age range to actually observe their experience.

Regarding Balefire Labs, not only did we not pay them anything for the review, but they have a process that involves transparent, objective criteria based on empirical research about the features of effective instructional design, and they have established internal checks and balances to make sure the reviews are objective – in particular, they have multiple trained reviewers apply the review criteria to a subset of their apps and compare those reviews for consistency (this is a check on what is called “inter-rater reliability”). I know of no other review service or site that goes to these lengths to ensure fairness, objectivity, alignment with instructional efficacy, or reliability.”

Hmn. Interesting. As cynical as I’ve become working on this summer series I can’t help but wonder if he was seeded as a sharpshooter or a covert shill for either one of those sites…Kidding, but see what I mean? Clearly it makes my point about the dangers of a jaded public flooded by sock puppets and native advertising duping consumers with bait and switch journalism.

Aside from conflicts of interest, misalignment and monetization models being helter skelter, there’s also the big elephant in the living room…

Do paid reviews even work? And if so how? More downloads? Awareness? Good will and public relations for building long term credibility?

Do Expedited Reviews Even Work?

Nancy MacIntyre of Fingerprint left a comment on Part One of the series,

“Sad to say, that our experience has been that most app review sites have little or no impact on sales or awareness of our apps. The exception is Children’s Technology Review and Common Sense Media – both sites without paid promotion and a rigorous process…The direct result of this is that we don’t pay for reviews or content posts with bloggers.

That said, paid reviews are no different than mobile or Facebook advertising to parents as long as the payment is disclosed. I like to think that parents are savvy enough to know that many of the products featured by bloggers / review sites are all paid for – whether through a media buy or other promo, which is no different than in the print world. The fundamental issue here is that app developers have few opportunities to promote their apps!”

(Amy’s aside: I’m NOT seeing that level of media literacy at all among parent purchasers whatsoever, we’ll get to that fix in a minute)

K-1 Special Educator and Reading Train app developer Libby Curran (blogging at KidSchema) also expressed a strong lack of “ROI” on paid reviews…

K-1 Special Educator and Reading Train app developer Libby Curran (blogging at KidSchema) also expressed a strong lack of “ROI” on paid reviews…

“I haven’t personally seen (or heard of) any recent connection between reviews and downloads, let alone sales, so no expectation of ROI*…Paid posts make it difficult to discriminate between apps that deserve a top review due to genuine quality and those which are included because of a payment.

Most sites say that they will only review high quality apps and that the reviews are honest, but it seems likely that the business model encourages a kind of “grade inflation” as it is hard to imagine that a lot of bad reviews would enhance a site or lead to repeat business.

It is difficult to tell on some sites which reviews are ads, paid press releases, sponsored posts, and expedited reviews. Taking payments for expedited reviews leads to long waiting lists for unpaid reviews (on those sites that still do unpaid reviews). This is bad for developers and consumers….A great new app can get missed completely as they wait for a review.

It is difficult to tell on some sites which reviews are ads, paid press releases, sponsored posts, and expedited reviews. Taking payments for expedited reviews leads to long waiting lists for unpaid reviews (on those sites that still do unpaid reviews). This is bad for developers and consumers….A great new app can get missed completely as they wait for a review.

Also…paid reviews, sponsored posts, ads etc. clutter the app review sites and make it very difficult to find good apps after they have been reviewed.

The sheer volume of information means that after a review appears, it gets lost on the crowded site. Most sites spend more time on reviewing than on curating and organizing. Discoverability is the biggest problem. Sure, when I search for my app by name, on the App Store or on a review site, it can be found, but if I already know the name of an app, I don’t need to search! If I search by age/grade, or subject, it might come up at #100, below apps with a bigger media presence but not necessarily of higher quality.”

*Libby Curran added her own stat specifics: “In Feb. 2014, a (free) review on SmartAppsForSpecialNeeds led to a small bump in downloads for about 3 days: 50-300, with a total increase of about 600 free downloads; unclear if that led to any sales as it wasn’t “trackable” back then. A second review on TeachersWithApps.com had no effect on downloads. Since that one time, they’ve had a few reviews with absolutely no change in downloads, likely “due to the huge increase in the number of apps and number of review sites over the last 2 years.”

Time and again, I heard firsthand stories, “the difference from when we paid and when we did not made no difference…”

So why would anyone bother to pay for “expedited reviews?”

The hope for traction, lift, credibility and buzz with increased awareness over time keeps app developers continually searching for the almighty grail, locked into the pay to play circular loop of make or break downloads and discovery.

I asked several app developers for their own stats like this, but few folks were as forthcoming. I wanted to see quantifiable patterns to see if paid reviews “even worked” and most expressed the universal conundrum that analytics are rarely available except to themselves, as no one shares the data openly. (if you *would* like to share stats/stories, I’ll update with comments, so fire away)

Reaching out for specific quantifiable stats to those who have both written and paid for app reviews, I received a considerable amount of “I would if I could” types of responses, with many expressing a hunch that the review lift is helpful, but no supporting data to back it up. Several have had comments like “I only have my own traffic data to go on, no info about sales is available to me for individual apps, unless developers share it…I wish it was open info. Everything about this industry is in separate silos that aren’t transparent, an issue I’ve mentioned in previous posts. It makes it very difficult for people entering the market to take its temperature.”

Carisa Kluver of Digital Storytime pointed toward helpful how-to resources, like a guest post on Digital Media Diet by Wasabi’s Amy Friedlander titled, “Paid App Marketing: Seven Priceless Lessons” and her own ongoing series looking at the marketing aspects of the app industry from the inside, out.

The most popular retort by far was that “The needle moved based on the writer not the expedited piece.” This reflects the credibility of ‘influencers’ often cited in this trust economy, the use of branded personas, and the clout that comes with reviewers and researchers leaping over both sides of the industry fence.

Talent Pools: Diving Deep vs the Shallow End?

The conundrum of making money to keep a great site alive is starting to create a mass exodus of many excellent “deep dive” reviewers, changing the talent pool.

The conundrum of making money to keep a great site alive is starting to create a mass exodus of many excellent “deep dive” reviewers, changing the talent pool.

What happens next is akin to a toddler’s pool party, the ones making the biggest splash are often just making a lot of noise flailing around in the shallow end…It’s their sheer numbers giving them presence. Standards and practices could use some lifeguards and resuscitation as well…One reviewer cited the rigorous testing that used to be commonplace when a pair of reviewers would try to replicate any bugs before sounding off, always subjecting apps to two sets of eyeballs, asking for two promo codes to test every app…

Now with the overwhelm of a flooded marketplace, formerly excellent sites are getting watered down (beholden to funders, foundations and ad revenue) or staffed with overworked reviewers doing the ‘churn and burn’ basics of word counts and star icons just to include it for ‘coverage’…

Indie sites writing with considerable depth and passion cannot function as a public service…as I personally know all too well. Sooner or later, something’s got to give.

Mass Indie Exodus of Respected Review Sites

Carisa Kluver helped delineate and validate some of the sustainability issues from her own experiences in the publishing/book world of reviewing iPad apps.

“Paid review services are extremely controversial in the book world but less so among app reviewers in my experience, so I find I have to explain myself primarily to those in publishing circles.

Ultimately I had to decide between shutting down access to my site or charging for expedited reviews. As ambivalent as I was about this move, I was much less inclined to shut down my site entirely.

Magazines & newspapers dealt with advertising restrictions around content in a previous era, so it may be part of the industry we have to accept, although today we can at least be more transparent about the influence. So my decision was to limit my paid reviews to no more than 20% of my total content. Even with the best intentions and non-partisan reviews, simply covering paid content creates bias, so I try to limit it to a small portion of my content – literally the amount to keep the site hosted.”

Carisa Kluver continued, “It should be noted that I also run my site by myself. One person. This means I cannot, after 5 years as a hobby, keep the site hosted unless I want to pay out-of-pocket for the privilege. The reality is that most sites are in the same boat. There is virtually no source of public funding for this type of service. If someone wanted to shame my site for taking pay-for-play reviews I could just shut it down overnight and go on with my life. The librarians, teachers & parents I serve would be very bummed, however.

Carisa Kluver continued, “It should be noted that I also run my site by myself. One person. This means I cannot, after 5 years as a hobby, keep the site hosted unless I want to pay out-of-pocket for the privilege. The reality is that most sites are in the same boat. There is virtually no source of public funding for this type of service. If someone wanted to shame my site for taking pay-for-play reviews I could just shut it down overnight and go on with my life. The librarians, teachers & parents I serve would be very bummed, however.

For a site like Common Sense Media, the expense for hosting and paying reviewers is much higher, so some sponsor must be found (Disney or otherwise) or the site cannot continue. Common Sense has PAID staff and reviewers (as they should). This is the difficult issue for so many sites, but something many site users are ignorant about.

There is a desire for good, non-profit information but little support for non-commercial services. This means users need to be savvy, thorough in vetting trusted sites and willing to wade through paid content. The other option is trial and error individually, which I suspect is how many people find good apps, unfortunately.”

How Can Parents Discover Helpful App Info?

Where do busy parents fit into this conversation?

It’s perplexing to me that I’ve heard ‘crickets’ from the massive online parenting communities I’m involved with when it comes to critical thinking about whether a review has been bought and paid with content marketing money…

Perhaps parents fall into the majority of media consumers who are unable to discern native ads thinking they are real articles…

…Or maybe they “don’t give a give a flying fig” as long as junior is happy…Or prefer the myopia of staying with a given apps review site they’ve heard of, obediently following like ‘sheeple’ without questioning the content…Or maybe they simply rely on word of mouth and trial and error which essentially means review sites in general are a null and void waste of time.

I’m not willing to believe this is ‘as good as it gets’…it’s too fouled up to leave the current system where it is.

So What’s Next? How Can We Build a Better System?

We’ve established we can’t compare apples and oranges and expect to cherrypick the good stuff with what’s ripe for kudos, when review sites start snagging low hanging fruit in bulk with ‘everybody wins’ machinations that result in a rise to the top of search engines by name mention instead of useful, trusted, hand-picked discernment.

We’ve established we can’t compare apples and oranges and expect to cherrypick the good stuff with what’s ripe for kudos, when review sites start snagging low hanging fruit in bulk with ‘everybody wins’ machinations that result in a rise to the top of search engines by name mention instead of useful, trusted, hand-picked discernment.

The way it currently stands, parents searching ‘by age’ could easily land upon a lightweight kids app reviewed in the early days of tablets as “five-star fun” with a few simple pages that go ‘sproing and baddabing’ and right next to it, see the exact same rating given to a complex, multi-dimensional app with immeasurable layers of engagement bells and whistles which has to compete in the sophisticated, uber-competitive environs of 2015. (For clarity, I’m referring to review sites not app stores)

How can they both be ‘the same’ without being evaluated under present day benchmarks and environs?

What about newly minted research on age/stage/child development or new studies on screen time with interactive vs passive play? Seems to me there are more than ‘apples vs oranges’ to cherrypick, there’s a whole fruit salad.

After all, criteria and rubrics have changed, technology has changed, star ratings and metric methods change and even the industry, parenting expectations and sites themselves have changed!

If stale app reviews are only updated when they’re bought and paid for, that stagnancy leaves a legacy of meaningless ‘star system’ ratings and content that makes it harder for today’s parent and educator to discern what’s worthy.

How CAN we all best assess reviews and find quality apps?

Even a simple “updated” snipe with a timestamp at least would help by showing there have been eyeballs validating a rating or adjusting it accordingly…

Maybe a simple iconic treatment could apply to the entire review process, similar to the privacy checklist of “Know What’s Inside” (which is now more policy/industry consortium than ‘moms’) which evolved from the icons at Moms with Apps.

An idea like this could be a helpful addition to denote at a glance what is/isn’t paid for, author bio, background of the reviewer and a timestamp for freshness…

I can almost visualize the icons already, a dollar sign $, a pen or pencil, industry tethers (a rope? handcuffs? ha!) Notations of crossover w/industry ties using icons for Google/MS/Apple teacher certifications, etc?

Jill Goodman a contributor to the AppoLearning review site cautioned that standardization can also make reviews become soulless and constrained, so parents need to know what to look for, and app developers need to do their homework:

“I read lots and lots of reviews each week. I actually hate rubrics. I find they yield very uneven results as some apps don’t fit neatly. Also what PreK needs isn’t the same as school age yet most rubrics don’t change for older kids.

My advice is ask whether the review covers strengths and weaknesses or just summarizes what the app does. Half the reviews I see just reword the info on the app description. If the only adjectives are cute and fun then I’d look elsewhere for a better review. If there is nothing critical then I’d be wary.”

![]() She goes on to say that she’s given apps five stars yet still shredded them for lack of diversity or not being universal, finding apps through all channels, from social to direct public relations pitches that land on her desk. She’s beta tested some early on, written descriptions for others, and emphasizes that app groups on LinkedIn are a great starting point, giving this advice for new developers:

She goes on to say that she’s given apps five stars yet still shredded them for lack of diversity or not being universal, finding apps through all channels, from social to direct public relations pitches that land on her desk. She’s beta tested some early on, written descriptions for others, and emphasizes that app groups on LinkedIn are a great starting point, giving this advice for new developers:

“I’d say invest some money in a pro if you’ve never launched an app. If your English is not fluent get help. Send a code. Don’t ask first. Yes some will net you nothing in return but some will. Use a clickable redeem now. Make it easy for someone to download it immediately from any device. Make an original app to start with. Too many developers make Toca Boca copies or other knockoffs and complain they make no money.”

Turning the Industry Inside Out: Apps Partnering Early

As I wrap up Part Three feeling like I’ve been through the ringer of industry stories turning ME “Inside Out,” watching app developers struggle to be seen and reviewers struggle for sustainability, I’ll close with some key questions about commercialism, monetization, and innovation…

As I wrap up Part Three feeling like I’ve been through the ringer of industry stories turning ME “Inside Out,” watching app developers struggle to be seen and reviewers struggle for sustainability, I’ll close with some key questions about commercialism, monetization, and innovation…

Has the hype and hope of trying to create the next app megahit been replaced with proactive partnerships and strategic deals early on, as indie app developers create their own hybrid deals to gain discovery in presence and massive mainstream ‘lift’ in mindshare?

Will branding become the new form of ‘expedited’ discovery?

Will product placement become the app survival guide?

Shudder. Talk about a case study that received a rocket boost… You can’t buy this kind of media coup, as the creators of Choremonster land in Fast Company and again in Time magazine’s money section with the headline “This App Will Have The Kids Beg for More Chores.”

Or can you? Is it a promotional tie-in with a side of content marketing for the media buy to earn top placement? Who knows? The reviews are almost TOO pitch perfect for parents…it almost whiffs of strategy and savvy. Again, these are the types of critical thinking questions we should all be asking ourselves regardless of which app or what media we’re consuming.

Backing up, what I initially thought was a small indie app (Choremonster) somehow smelled a lot like big money, smart placement and media branding and I couldn’t place my finger on why…

I sniffed around the media literacy money trail and though I still don’t know the full scoop on what is/isn’t paid for content marketing/press coverage wise, the product placement deal altered the whole focus of the app from my lens. This sentence is worthy of trend tracking alone:

“Through a tie-in with Disney, ChoreMonster parents were able to reward kids with exclusive pre-release clips of the Pixar movie Inside Out in May and June. The company says it was a popular reward, and that other partnerships and unusual tie-ins will follow.”

Small indie app meets big media tentacles with clout, cash, and brand building big time…Sure enough…

Tracing back a year earlier, turns out ChoreMonster was one of eleven startups in the Disney Accelerator program with access to mentorship and creating fresh monetization models, in their case giving away the app for free by partnering with brands rather than taking a subscriber route. All planned and paid for…The cross promotion (and product integration) of the ChoreMonster app with Pixar’s Inside Out gave me a big ‘aha’ media literacy moment this summer…

What does this mean for indie endeavors?

Is innovative alignment with brands and big corporate media players the future of indie apps?

Will nonprofits or indie apps organizations lobby for a centralized vetting site staffed with seasoned pros?

Will creators begin to solicit big media and tech partners at the onset?

Will commercialism infiltrate more offbeat apps or overshadow smaller enterprises that have a more thoughtful presence?

Will new models surface so app creators can sustain themselves or is selling out to Goliath the corporate credo?

Thoughts? Concerns? Industry improvements and ideas? Lob them into the comments…

It’s been an insightful, wild ride to learn about the kids app industry, from the “Inside, Out.”

Ancora imparo on all things app! It’s Back to School for me…

Visual Credits: Short tail vs long tail illustration, Hugh McLeod, GapingVoid.com Cherries via zaveqna on Flickr, Cruise line poster by Wetcake Studio via VintageTravelPosters.co, Star rating comic: Randall Munroe via Bradley Grimm, Libby Curran w/kids photo via Learning Center +article on appolicious; Anchor graphic via Polyvore/ETSY; There’s an App for That graphic: Soshable.com/app-overload ’11, Eric Carle screenshot Very Quiet Cricket; Transparency via Shutterstock, money talks graphic ’08 anunciosgratis.cl; Best apps trophy app via TinEye-DepositPhotos/stock photog; Inside Out screenshots via Pixar/Disney

> Hmn. Interesting. As cynical as I’ve become working on this summer series I can’t help but wonder if he was seeded as a sharpshooter or a covert shill for either one of those sites…Kidding, but see what I mean?

I’m not taking the bait here other than to state for the record that I am not a shill for anyone. In particular, I have no financial or other ties to Balefire Labs or Teachers with Apps outside of our business relationships. It’s easy enough to Google me or take a look at my education blog (http://theeducationscientist.blogspot.com) and make your own judgment based on what you find.

Here’s the core problem in this space as I see it…

We actually have two different educational ecosystems co-existing.

Consider the cosmetics industry for a moment. They manufacture a luxury good that people can choose to consume or not. The manufacturers and distributors can pretty much say whatever they want to convince people to buy their product – it will make you more beautiful, make you feel more confident, make you more desirable, and so on. Whether anything they say is true or not is hard to know, and they are clearly paying influencers (celebrities, for example) to promote their products independent of those people’s true opinions about the products. These are similar behaviors to what we see in the education space. So why should we consider it a problem in education but not here? The perception in the beauty industry is that the worst case scenario in beauty is if someone buys a product and is disappointed that it doesn’t deliver as expected – the cost is their disappointment and some wasted discretionary income. Caveat emptor – buyer beware.

Now consider the medical domain. Once upon a time, people could claim anything – that they had a pill to cure cancer or baldness, for example – to get people to buy their product. Today that’s not allowed. We have organizations – both formal organizations like the FDA and informal organizations like watchdog groups – that make sure people can back up their claims and that proper disclosure guidelines and safety mechanisms are in place. Why is this different from cosmetics? Because the consequences are higher – taking the wrong medication can make a person sick, sicker, or even dead.

So, it’s evidently ok to say whatever you like to get people to hand over their money when the stakes are low, but it’s not ok to mislead them to death.

The problem in the educational sector is that there’s a lot of money in the system, which attracts a lot of profiteers. They behave as if the stakes in education are more like the stakes in cosmetics. (After all, they reason, I am beholden to my shareholders on the financial side, no one is really looking too closely at what I’m doing on the education side, and what’s the worst that can happen on the education side anyway?)

There’s a whole group of us who are drawn not by the profits but by the mission. We see the stakes in education as more like the life-and-death stakes in medicine than the “mild disappointment” stakes of cosmetics. Indeed, it should be obvious (and there’s evidence to back it up) that poorer quality education from pre-school on leads to higher crime, more violence, more prison time, higher rates of teenage pregnancy, greater poverty, more frequent and more severe illness, higher stress, greater political disenfranchisement, and a whole host of other nasty outcomes. One problem is that while the damage from educational snake oil may be inflicted immediately, the effects are hard to trace back and in most cases won’t be evident until years later, and then only indirectly.

But we mission-minded people who understand that it’s not ok to trick people out of their money (or, perhaps more importantly, their precious learning time) in education any more than it is in medicine are at a huge disadvantage. It’s much harder and much more expensive to build educational technologies that actually work than it is to build some edutainment fluff and slap an educational label on it. In principle, we should also be conducting independent evaluations of whether products do in fact work and that they don’t in fact harm the learner (yes, it’s entirely possible to do more damage than good with bad educational interventions) – that’s a huge additional expense. After we do all of this work and invest all of the resources required to get it right, we get to the reviewers. Many of them are basing their decisions on how many flying monkeys the application has, or whether it has some newsworthy novelty factor that is completely unrelated to its educational value, or how much money is in it for them (directly or indirectly). The few mission-driven reviewers who authentically try to develop a rigorous, objective, ethical process for discerning the educational value of an educational product face the same hurdles as the mission-driven product providers. Educational efficacy is somehow not what the majority of people recognize as the primary value of education, and so the system doesn’t select out the reviewers who would help select out the providers who are providing the high quality educational products.

See the problem?

These are two separate ecosystems co-existing – one is financially oriented and the other is education oriented. These are two completely different species, but to the consumer they are largely indistinguishable because right now all they have to go on is the provider’s word for it – and how compelling the provider’s word is depends strongly on the marketing budget. The former dominates, but tends to produce snake oil (or junk food, if you prefer that metaphor).

What should we do, you ask?

Step #1: Clearly distinguish among the species of education providers

1) Profiteers – in the extreme, they will do anything to maximize profits, educational impact is not a real consideration, and products are of unknown or dubious educational value; often there is little or no actual educational expertise involved in the making of their products; the “educational” label is applied as a marketing tactic; may be VC-backed (generally a red flag in education)

2) Educators – need a sustainable business model that generates enough revenue to support their mission, but always prioritize the needs of education stakeholders over shareholders; top priority is educational impact; educational expertise is at the heart of the organization and drives the product development process (instead of financial and technical considerations driving the product development process)

There are many hybrids. Edutainment providers are probably the biggest hybrid segment – their organizational motives may range from mostly profit to mostly educational impact, but in terms of design the top priority is entertainment value, not educational value. They may have educational expertise in the mix, but it typically is not defining the agenda. The reason there is so much activity here is because there is a pervasive misconception on both sides that if a child appears to be engaged and we clearly state our good intentions for them to be learning something useful (like spelling or addition) then that is a recipe for effective instruction. This is magical thinking, but both the suppliers and the consumers of educational products seem to assume it is true and so there’s a meeting of the minds where consumers will actually pay providers for this kind of material and so these providers have a fighting chance to survive.

Step 2: Clearly distinguish among the species of reviewers

1) Education reviewers – have educational expertise at the core of the organization, top priority is educational efficacy, have principled review criteria that are demonstrably related to educational efficacy, ideally have an objective process (with inter-rater reliability so that if you review the same app twice you are can be confident you will get a very similar review), have a firewall between the functions that handle the money (ads, expedited reviews, etc.) and the functions that handle the reviews – ideally, the reviewers should not know which reviews (if any) have been paid for and which have not; are constantly looking for high quality educational apps, whether they are paid to review them or not; by the way, this is not to say you can’t evaluate engagement value of an educational product as part of this – just that it can’t be the only or dominant consideration

2) Edutainment reviewers – everyone else; this includes edutainment reviewers who are evaluating an app based primarily on its entertainment value, individuals or groups with technical or entertainment expertise but little or no educational expertise, individuals or organizations with ad hoc review criteria – or no fixed criteria at all but just write up their in the moment reactions to an educational product; organizations with ad hoc review criteria that have little or no demonstrable connection to educational efficacy, reviewers with low reliability – if they were to review the same app twice they might give two wildly different reviews; and so on

Now set up two pipelines like we have in the medical domain:

1) the “prescription education” pipeline that has formal criteria for qualifying which products and reviewers are included, has clear labeling guidelines (e.g., defined learning objectives), a body of efficacy research, and so on, and

2) the “homeopathic education” pipeline that has no formal requirements for inclusion of either products or reviewers, doesn’t require labeling, is free to prioritize entertainment value over educational efficacy, free to prioritize shareholders over educational stakeholders, and so on (this would include the great majority of the current app stores and review sites)

This segmentation and alignment would enable people who are really serious about education to find what they want and to support the organizations (providers, reviewers, etc.) who are serious about solving educational problems and providing quality educational products while allowing other people to pick what they like – those who are actually looking for an app that has high entertainment value (will occupy a kid for a long period of time), for example, but that they don’t have to feel too guilty about (because it makes some plausible claim to providing education).

A major problem right now with everyone being thrown into the same bucket is that the questionable tactics of some profiteers spills over onto everyone else, jading the end users and eroding trust in any provider (except, strangely, those with the most established commercial brands and the largest budgets for marketing, independent of whether they have any educational expertise).

@Michael Connell:

Enjoyed your medical analogies (as well as the vehicle ones on your education scientist site too) as you strike like a rattler at many of the core issues plaguing the education arena.

Fwiw, that apps/credibility analogy crosses over to problems in the public health sphere too (w/distortion of trust/differing levels of practitioners from misaligned MDs/nutritionists/RD/food science research w/vested interests parroting the corp ‘energy balance’ hooey to satisfy junk food stakeholders/lobbyists in school guidelines etc.) But I digress…

First, as you no doubt surmised, I Googled the heck outta you FIRST to make sure I felt comfortable poking the underbelly of critical thinking in our culture (or lack thereof) knowing it might ‘bait’ (I prefer inspire) more substantive discourse on how to engage those seeking solutions over rhetoric, blame games, and mental floss…so THANK you for playing along.

I particularly enjoyed the commentary about “distinguishing among the species of reviewers” with the idyllic firewall concept of reviewers not knowing what is/isn’t paid for (presume you’re referring to portal hubs where the reviewer is ‘assigned’ vs direct contact which negates the whole premise, though sadly that’s where we are right now with the mixed buckets so to speak)

You’ve made a strong case for trying to lasso the ‘effectiveness’ components of education (vs edutainment) and hope it will also fuel new discourse on how EFFECTIVENESS is defined, as elite educators jockey for how assessment is quantified and qualified given diff learning patterns/beliefs/methods on participatory/collaborative learning, informal edu, engagement etc.) There’s a lot of fuzzy factor in shades of “depends on what the meaning of the word is, is” on a wide array of kids media/digital fronts.

As one who is a media literacy wonk falling into the “I don’t have a horse in this race nor do I remotely pretend to be in the education realm,” I applaud your attempt to reduce the Tower of Babel and empty the slush buckets so parents can at least attempt to discern what trough they want to drink from (and which ones have flies buzzing). I think we all agree the clarity and transparency is sorely lacking in the big business/high stakes education of youth in or out of school environs…Giving voice to these important conversations and uncorking (ok, prodding) those directly involved is at least a starting point; that’s MY goal.

Appreciate you taking the time to feedback. Here’s to more lenses, diff views and considerable comments to come…

p.s. Ironically, in other parallels with the indie vs commercial kids apps/universe in today’s Sunday Chronicle, the topic of large corporate behemoth buyouts of small artisan food ventures puts forth the question once again…

“What gets lost when David gets bought by Goliath?”

Interesting read with multiple media parallels: http://www.pressreader.com/usa/san-francisco-chronicle-late-edition/20150913/281487865132653/TextView

So much good digging and understanding here but I’m still not certain where you come out except maybe “it’s complicated” and “caveat emptor”

Maybe it’s important to step back and remember that unlike in most industries, the majority of people who are in education get into it for the right reasons. Not everyone of course. And sometimes money does change people. But even though I’ve personally seen some things I don’t like, and read some things from you that make me cringe, I still believe that most educator-writers are inherently good people who want to serve children. The industry could do better and bad behavior deserves to be exposed, but we still want to put in perspective that if we are looking for true villains or folks just in it for the money ed tech review sites are an unlikely place to find them.

True, Nancy, but to me it’s not about villains and heroes…(and definitely not all about ‘education/ed tech’ so I’ve probably tried to paint with too broad of a brush, as there are nuanced aspects of the impact on indie innovation when large firms dominate the landscape.

In some cases it can enable a larger lens and ability to scale globally…when multinational giants back startups apps/tools/platforms etc. but in other cases it squelches/stifles/stomps smart thinking struggling to get a creative toehold. You’re right, the critical thinking/caveat emptor piece is probably MY focal point for media literacy, as right now we have a glaringly distorted intake with an abominable lack of transparency when it comes to purchasing power of parents (and perhaps educators) in terms of what’s worthy out there…

p.s. The subscription model to access/obtain reviews (such as your site) is a whole diff post altogether…(and one I’ve already started on paywalls, customization, tailored preferences, etc. I started to lump it into this post, but at 5000+ words this is beyond “TLDR” and I decided a separate entry about specialized learning w/diff media models is probably warranted)

Unfortunately, money really has an impact on people. I’m not into kids app industry at all and I was shocked to experience these insights.