Mar. 7, 2015 Selma March, 50 years later, commemoration of Bloody Sunday. #Selma50

Anyone who has seen the movie “Selma” knows the split second power of media storytelling to jolt viewers into a visceral, emotional sidewinder.

The teens on either side of me were wide-eyed, visibly shaken, and riveted as the dialogue shifted from children playfully bantering about hairstyles to the surreal scene of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.

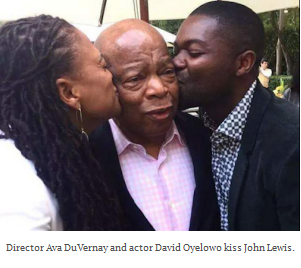

One flung her hands to her mouth as if stifling a scream, the other let out an audible gasp. Neither had proper historic context to even remotely see it coming, and it dawned on me that Selma director Ava DuVernay’s brilliant empathy lens managed to grip youth with an educational shoulder shake while making them care profoundly in a blip of a nanosecond. Nattering nitpickers of DuVernay’s chosen lens miss the poignant depiction of painfully raw realities that manage to plop viewers smack dab in the civil rights battlefield to give a damn. That’s powerful media.

Selma captures empathy as an art form

DuVernay takes Windex to the blurred, desensitized distance often depicted in grueling war torn biopics laden with special effects, and instead uses her prowess to touch upon shared pathways in the desire to elevate the human condition…

DuVernay takes Windex to the blurred, desensitized distance often depicted in grueling war torn biopics laden with special effects, and instead uses her prowess to touch upon shared pathways in the desire to elevate the human condition…

In short, she gets up close and personal and won’t let us look away.

I found myself profoundly attached to every single character in the film, not just the leads, as wince-worthy tensions escalated with each scene of injustice, provoking an “omg, no, not him…please…not her…” style of response. Her restrained finesse with imagery and non-gratuitous violence left our own imaginations brutally deployed, as tears welled within me again and again connecting to the human, personal stories that seared into my soul. The Glory soundtrack and finale newsreel footage of “Selma is now” elevated the film to empathy as an art form.

John Lewis, living history via film

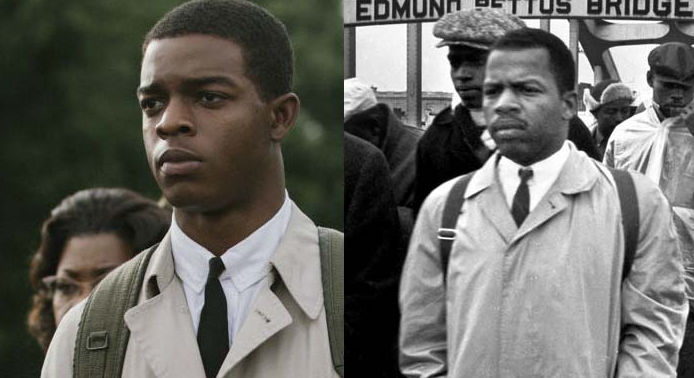

‘Boots on the ground’ style storytelling gleaned from those who have ‘been there done that’ has a remarkable impact on kids. (see Phactual.com’s split screen examples, like John Lewis in the Selma movie, and in real life).

It’s the kind of relatable storytelling that makes people care…the next best thing to ‘first person/you are there’ experiences told in life’s own ‘reality TV’ that cuts through the clutter to engage youth directly, powerfully.

For me, Selma as media conduit struck a refreshing female director’s tone that made this sort of narrative honest and appealing, provoking conversation, observation, media literacy exploration and the opportunity to dig deeper into icons of living history from the era, to hear their “then and now” lens firsthand.

Now…Can graphic novels like March evoke similar emotions?

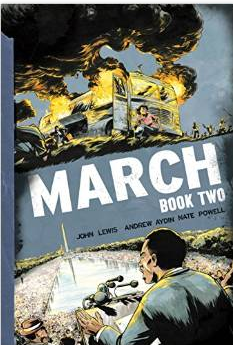

At first it was hard to fathom how Rep. John Lewis’ graphic novel series could impart such important subject matter via cartoon bubble, telling the story of Selma through graphic novels without looking like a BIFF! Kapow! Blam! style DC comic.

At first it was hard to fathom how Rep. John Lewis’ graphic novel series could impart such important subject matter via cartoon bubble, telling the story of Selma through graphic novels without looking like a BIFF! Kapow! Blam! style DC comic.

I was more than a little curious how the illustration of artist Nate Powell and the narrative of Rep. John Lewis and legislative aide Andrew Aydin would manage to tug at the same evocative e-quotient to extract empathy with accurate depictions of the heinous brutality of civil rights struggles in Selma instilling the strong stance of nonviolence he wished to convey from his own experience.

But somehow, they did it. And they did it well.

It’s a complicated feat to keep a natural tone, lace in anecdotes and factoids, stay accurate and speak truth to the movement’s many iterations through the lens of a current day congressional representative’s own personal pummeling, tear gassing, jail time and trampling, while reiterating a message of nonviolence.

But each edition of this trilogy manages to March on where the last one left off…

March is substantive and compelling

The “March” books embrace a fast-moving, 21st Century non-linear style, zinging between the seeds of student uprising, the faces and phases of civil rights clashes and embroiled shifts in leadership, the present day progressions with President Obama’s inauguration in 2009 and even looping back to Rep. Lewis’ own childhood on his family’s own sharecropper farm, where he tells tender, elaborate stories about the naming and care-taking of his chickens.

Though in black and white, every passage paints a colorful picture, sharing bits of personalities, profile quirks, emotional baggage and political snippets of the movement via montage.

Intricately woven backstory and threads of his own character development surface, moving the reader with a behind the scenes point of view. Snapshots of Lewis’ own autobiography make the books come alive…

Imagine young John Lewis creating his own makeshift incubator while dreaming of a real one at an unaffordable $18.95 from the Sears wish book. From chicken eulogies and preacher aspirations to farm pets like Lewis’ favorite L’il Pullet, who followed the leader, the textural details woven into the storyline particularly appealed.

“Maintain eye contact, John!”

The drama in the graphic novels slice into history with a fresh blade…edgy, timely, relevant, classic page turners. Stories abound with white thug skirmishes, the menacing gravity of the KKK and being hosed and fumigated like pest control…

There’s the pensive decision to march on amidst high stakes danger and stubborn pride…Power plays, police politics, and tenacity of not backing down at critical crossroads of the voter’s rights movement…

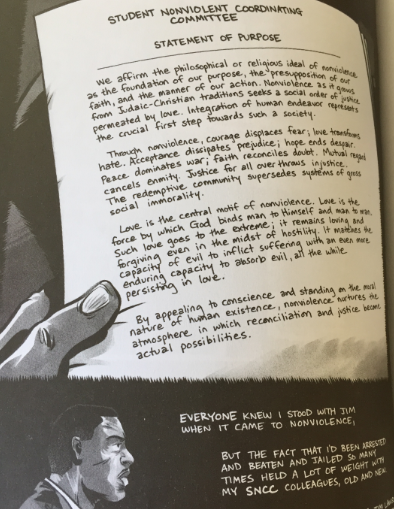

One of my favorite passages shares the SNCC strategic tactics of nonviolence training workshops where the students purposely role-played to try to dehumanize each other and break each other’s spirits to prepare for their peaceful stances against segregation at lunch counters, movie theaters, as Freedom Riders and crossing the bridge in Selma.

One of my favorite passages shares the SNCC strategic tactics of nonviolence training workshops where the students purposely role-played to try to dehumanize each other and break each other’s spirits to prepare for their peaceful stances against segregation at lunch counters, movie theaters, as Freedom Riders and crossing the bridge in Selma.

Cartoon bubbles implore with safety warnings in a ‘you are there’ experiential flavor, reminding how fast humanity can devolve into depravity once ‘object’ status kicks in over face to face connection and humane outreach.

“Jim Lawson taught us how to protect ourselves, how to disarm our attackers by connecting with their humanity, how to protect each other, how to survive…but the hardest part to learn—to truly understand, deep in your heart—was how to find love for your attacker.”

The narrative devices show attention to detail and capability of artistic elements to stir the senses.

The narrative devices show attention to detail and capability of artistic elements to stir the senses.

Repeated use of phone icons end each book and leave you dangling (in book one it’s a depiction of an incoming cell phone call vibrating, in book two it’s the pay phone cord from a booth blown off by the blast which is depicted in the closing frame of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church) The degradation in the jail cells is palpable, and the ‘in your face’ singing and defiance is uplifting and inspiring. The emotional content moves the reader through the story arch with shadows and echoes of the Ferguson urgency tempered by the vast differences of the times and a useful primer on nonviolent ways.

March makes history visceral, approachable

Beyond March’s graphic ability to make tough subject matter approachable, in the words of Lewis himself:

Beyond March’s graphic ability to make tough subject matter approachable, in the words of Lewis himself:

“March: Book Two is making it plain, making it real so young children will be able to see this book –not just read it — see the drawings and feel it”…

It also helps pique interest in delving deeper, bringing history to the forefront with personal storytelling, unearthing follow ups with living icons in ‘where are they now’ mode, as the graphic novel mentions names threaded throughout the books like a ‘who’s who’ primer of activists of the era.

The powerful series gives many students vision, hope and nonviolent contextual relevance juxtaposed against today’s headline news, though it almost didn’t see the light of day. Lewis’ young Congressional aide (now co-author of the series) Andrew Aydin brought forth the youth lens early on, seeding the idea of connecting with young people through fresh new channels of storytelling, bringing a Comic Con “why not” approach, explaining in this Yahoo news piece,

“I was too young to know any better about whether or not it was appropriate to even pitch a member of Congress, much less an icon, on doing a comic book,” said Aydin, who joined Lewis in a joint-interview…Though Lewis initially resisted the idea of writing a comic book, Aydin persisted.

“He kept coming back,” Lewis recalled. “And I recalled when I was only 18 years old I read a comic book called ‘Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Montgomery Story’ — that book changed my life.”

Co-authors John Lewis and Andrew Aydin have recently been on the university circuit igniting a whole new generation through tempered, nonviolent action as a catalyst for change.

“After a grand jury decided not to indict the white police officer who shot and killed unarmed black youth Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., last year, students in Louisiana created an organization modeled on the national student movement Lewis led, because they’d read about it in his first book installment,” Aydin said.

“They could all benefit about understanding how nonviolent protests succeeded in the past in pressuring political leaders to act,” Aydin reminded.

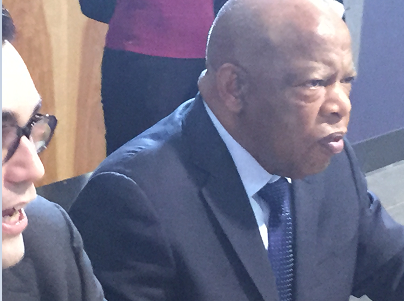

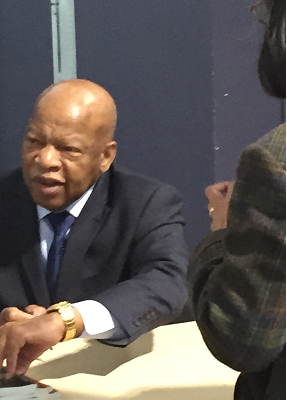

I was lucky to meet them both, downright giddy, in fact.

I was lucky to meet them both, downright giddy, in fact.

The thought of hearing John Lewis himself (now Congressional Representative/GA, then SNCC chair) delivered the same awe-inspiring clout as when I had the opportunity to meet John Dixon expelled from ASU over the civil rights lunchroom sit-ins in 1960.

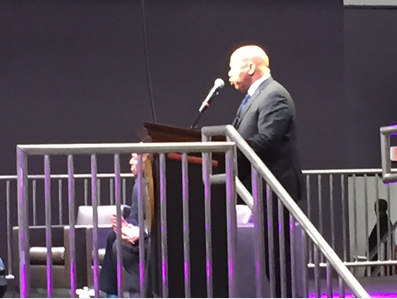

Speaking at San Francisco State University about nonviolent protesting while sharing his newly launched Book 2 of his graphic novel trilogy “March” (copies were given gratis to SF Unified School district and collegiate students attending) I was amazed by both his oration and the translation of his experience into what might initially brush off as ‘comic book’ form.

Listening to John Lewis share his own brushes with death, firm in his convictions to create “good trouble” and snap open ‘eyes wide shut,’ 50 years melted away and living history landed front and center on stage.

Listening to John Lewis share his own brushes with death, firm in his convictions to create “good trouble” and snap open ‘eyes wide shut,’ 50 years melted away and living history landed front and center on stage.

The Southern Poverty Law Center, in a 2011 report, “Teaching the Movement,” found that 16 states didn’t require instruction about the movement, and in 19 others coverage was minimal, while most states failed to teach that era well, as this piece cites hundreds of schools already using the first “March” book to fill the civil rights edu-chasm in coverage.

It’s no surprise then, that you could hear a pin drop in the audience, as students eagerly listened to Rep. John Lewis’ first person pointers from an era many have barely heard ‘taught’ in schools beyond the lionized Martin Luther King Jr. snippets and broad brushstrokes of civil rights leaders long gone, burying topical problems of race and cultural credos as if ascribed to an era long gone.

This dynamic duo resurrects the relevance into a 21st century change agent lens filling the chasm of educational gaps in teaching about the era of civil disobedience, and freshening resolve anew.

Just like the Selma movie itself, the books are a starting point to a much larger conversation, with the bravery, courage, and ‘put yourself in this picture’ empathy lens that serves as a pivotal role in framing not just the problems but the ongoing solutions that MUST surface in the national dialogue on race and social justice for change.

Just like the Selma movie itself, the books are a starting point to a much larger conversation, with the bravery, courage, and ‘put yourself in this picture’ empathy lens that serves as a pivotal role in framing not just the problems but the ongoing solutions that MUST surface in the national dialogue on race and social justice for change.

I personally used both the movie and the graphic novel as springboards to find out more, whether it was firing up the actual audio archives of conversations between LBJ and Martin Luther King Jr. (yes, these crackly archive files are internet ready for your media literacy listening pleasure!) or Googling the ‘who’s who’ of activists from the era in ‘where are they now’ mode to hear some of the stories never told. (Did you know there was a fifth little girl in the 16th street bombing, who survived, for example? Why has her story been left behind, and only resurfacing to the media forefront now?)

Fast forward to media literacy pros like Frank Baker who referred me to the March books…He uses this series regularly as a strong proponent of the graphic novel genre for teaching visual literacy. (He also shares excellent resources for exploring the language of film, from the director’s lens with analysis in his media literacy hub.)

The ability to use media to explore essential questions and engage and inspire kids with “walk in these shoes” firsthand storytelling experiences brings learning alive far beyond the solemn salutes to slain civil rights leaders, and gives much needed context to the vitriol and polarity of some of today’s media coverage and important hashtag activism.

Yes, #BlackLivesMatter and Lewis and Aydin are here to do some schooling on the nonviolent message of being the change…in the present, not the past.

Related Reading by Amy Jussel, Shaping Youth

Selling Reluctant Readers: 10 Marketing Tactics to Amp Up Fun (inc graphic novels)

Meaningful Manga: Graphic Novels & Growth

Reading Rockets Kids Into Their Future (Pt. 1 Kalimah Priforce)

Visual Credits: Screenshots and iPhone photos my own/SFSU event, John Lewis split screen shot-Phactual.com; Selma trio: Ava D., John L., David O. via crewof42.com

Your readers may also be interested in Teaching Visual Literacy With Civil Rights Images

http://www.frankwbaker.com/vis_lit_civil_rights.htm

and

http://www.frankwbaker.com/images_of_civil_rights.htm